Athletics foster mental stability, yet mental instability impedes performance.

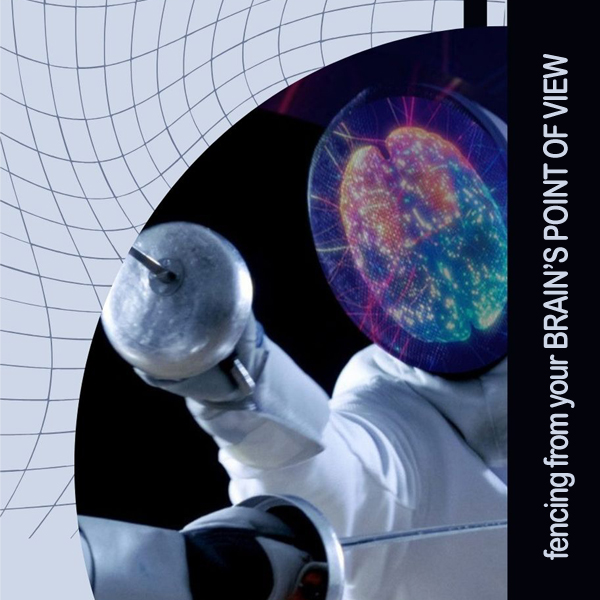

Sport is with no doubt very important for brain functioning as well as mental health, but young athletes are more and more living with stress nowadays and the pressure of competitive sport can actually have a negative impact on their brain. College and elite athletes have sports psychologists working with them. Youth fencers often do not. This bars them from mental training during developmental years. Understanding brain functions can help youth fencers and their families unlock solutions — from nutrition and sleep to mindfulness and breaks — for mental challenges.

- NEUROLOGICAL COMPONENTS

- Practice/Reflexes/Motor Control/Brain Mapping (learning and practicing)

- Unconscious procedural memory (not conscious, like episodic or fact recall)

- Increase in gray and white matter (more connections) when learning

- When learning, you need active planning and analyzing

- Increased activity in basal ganglia and premotor cortex

- ^^ decreases tremendously with increased practice

- With more overall proficiency, even learning new techniques becomes more automated because existing pathways are basically being rewired/modified, less planning during execution

- Reinforced pathways with practice

- Coordination between visual and motor cortices

- Brain mapping

- Combination of visual and somatic stimulus for your brain to create and reinforce a “3D image” of your body (include example about “falling asleep” leg)

- More neuronal matter for different aspects of body map depending on habits and activities (more representation for left hand in musicians; more detailed and finely attuned muscle control)

- Altering the way/environment in which you practice motions may help to better solidify them and make them more adaptable

- Focus in optimal performance

- Flow mode

- Alpha frequency (8-12 Hz)

- Bypassing consciousness; actions performed away from prefrontal cortex; input-output

- Distorted sense of time

- Complete concentration

- No self and physical consciousness

- Stop worrying and hesitating

- Necessary components: high challenge + high confidence for a specific FLEXIBLE, SPONTANEOUS goal + uncertainty of outcome + initial positive event (positive feedback) + “pushing it up a level”

- Get in: positive distractions (redirection from prefrontal cortex)

- Total absence of analytical thoughts

- Enjoyment in the moment (intrinsic)

- Clutch Mode

- More high-pressure, direct, imminent, scarier goals

- Ability to not fall apart under performance anxiety and follow through on what needs to be done

- Components: sense of urgency (close to fight-or-flight); awareness of situational demands + fixed goal + “switching gears” into increased effort/intensity

- Absence of negative/failure thoughts rather than absence of thoughts generally

- Enjoyment after (upon reflection)

- Get in: small goals and compartmentalization; battling complacency; self-monitoring and discipline; conscious self-motivation

- Flow mode

- Strategy/Analyzing opponent and planning

- Prefrontal cortex

- When goal-directed (not habitual) it is conscious, not reflexive

- Estimating outcomes and determining the usefulness of those outcomes

- Episodic memory (hippocampus; previously rewarded action); i.e. contextually appropriate response

- Reinforcement learning (strategy will inevitably and naturally become better through continual exposure)

- Practice/Reflexes/Motor Control/Brain Mapping (learning and practicing)

- CHALLENGES

- Depression/lack of motivation

- Feeling flat/under energized

- What helps:

- Not enough dopamine for optimal neuronal communication

- If chronic and severe: may require medical attention and/or drug treatment

- Unlike performance anxiety and other “psych out” issues on the strip, depression may actually hinder your ability to execute the motions properly, not just impact how you feel. Not enough dopamine means not enough motivation, but it is also the primary hormone through which your neurons communicate, meaning that all of your cognitive systems are slowed.

- What helps: therapy and medication (if a disorder); if temporary/related to loss/injury: taking breaks to allow your hormones to reset, focusing on restoring your physical health without overworking yourself

- Anxiety/external pressures (time, college apps, etc.)

- The yips and analysis paralysis

- Performance anxiety which causes overthinking; pfc is no longer bypassed during execution of habitual actions, thereby slowing them down and/or messing them up; also contributes to hesitation and impaired judgment (rushing/impatience)

- What helps: distraction, breathing techniques (for fight-or-flight)

- Chronic anxiety

- In a bout, you are never stressed about losing because of college or your friends’ reactions. Those ideas are too abstract for your brain (especially a competing brain) to be even remotely processing in that moment. You are only stressed by things that are immediate and/or previously traumatizing (for example, if you’ve had negative experiences taking a parry-six before, you may seize up when taking that parry).

- Chronic anxiety only comes into play because of its somatic effects:

- Spiked cortisol levels → inflammation and MUSCLE TENSION (messes up purely physical execution of actions)

- What helps: active stretching and adequate warmups, conscious relaxation techniques during movement practice to prompt motor cortex rewiring (away from superfluous muscles, like tensing your shoulder during an extension when it isn’t necessary for the movement itself)

- Chronic cortisol impedes hippocampus and can actually induce atrophy (messes up strategy but not reflexes)

- What helps: more difficult; if chronic and severe may require medical attention; viewing fencing practice as a leisure activity, like playing a video game, can help your brain relearn and associate the sport as an endorphin and dopamine booster rather than a stressful activity

- Identify and mitigate other stressors outside of athletics, like relationships, school, etc.

- The yips and analysis paralysis

- Underoptimized brain (sleep, nutrients, etc.)

- Sleep deprivation: when you sleep, brain goes through motions of its routine activities, essentially practicing them through the relevant neural pathways, but keeping you unconscious and paralyzed while it does so. The more deep and REM sleep you get, the more opportunity for your brain to rehearse the skills you’ve been learning and repeating — the faster newly learned abilities become reflexive and easy to use.

- Nutrient deficiency: your brain is an organ. Like the rest of your organs, it needs proper nutrients, so that its cells have the resources with which to keep functioning optimally. Certain vitamin deficiencies can cause you to feel less awake and aware, contributing to brain fog and perceived thought lag.

- Vitamins D and B12, iron, magnesium, omega-3

- Depression/lack of motivation